Sri Lanka: The urgency of bearing witness

First they were captives of a conflict in which their freedom and security was thwarted at every turn. Now huge numbers of the Tamil population of Sri Lanka find themselves trapped again, unseen for the most part and wholly unprotected.

The conflict may officially be over, but the battle to reach the victims is not. Aid agencies, the media and even the Red Cross have all been denied access to the military-run camps where an estimated 300,000 civilians are languishing in dangerously impoverished, hostile conditions.

The Sri Lankan government maintains that it will resettle those currently interned, describing its battle against the Tamil Tigers as "a humanitarian operation to safeguard the people of the area". But the reality is far different.

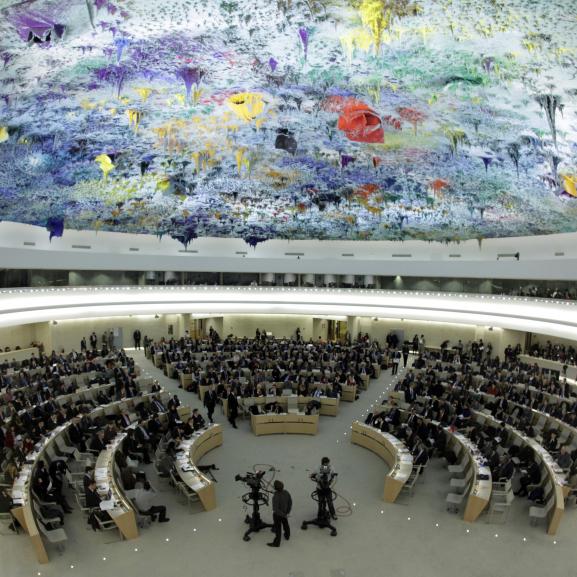

The UN has accused the Sri Lankan government of waging "a war without witnesses". While those still locked inside the camps are prevented from speaking out, the testimonies of those who were fortunate to survive provide ample testimony to a worsening humanitarian crisis.

Since 2006, when the peace process was finally abandoned and northern Sri Lanka was once again gripped by conflict, waves of survivors have sought help from the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture (MF). In 2005, before the e re-escalation of the conflict, just 50 people were referred. By 2008, that number had almost quadrupled to 187.

Stories of rape, sexual abuse, burnings with hot irons and long periods of solitary confinement are commonplace. All parties to the conflict, from the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) to the police and paramilitary groups, have been implicated. The Sri Lankan army is particularly notable for its appetite for torture. Yet the army has evaded an investigation into its actions during the war and since, in the military-run camps now being operated in the north.

One of many young Tamil men to have survived the notorious military-run Joseph Camp in Vavuniya is fretful about the fate that may have met the family he was forced to leave behind when he fled Sri Lanka last year. He was detained by the military during one of many sweeps that the authorities made of Tamil Tiger controlled areas, picking up young people regardless of whether they had any active involvement with the LTTE.

He was beaten and sexually abused almost daily for the two months he was held. He was never allowed out of the bare cell in which he was kept, but he vividly recalls hearing the screams of other Tamils, particularly women, being tortured.

Just one week ago, he spoke to a close friend who is still detained in an army camp in the north, who told him of life in the barbed-wire surrounded camps, where there is practically no food and people are treated like animals: "Tamils are dying and disappearing, this is a genocide that the government is aiding and abetting and nobody has lifted a finger to help while our people are being butchered.

"We need the whole world to put pressure on the Sri Lankan government to give access to foreign countries otherwise most of the people will be killed before anyone sees. They should give access to the war zone to see how many people have been buried there and to witness what life has been like for so long amidst all this destruction.

"I don't believe anything the government says now about protecting the Tamils - after the experience that I had when I hadn't even committed a crime, I cannot believe them now."

Any aspirations that the younger generation of Tamils had to build jobs, careers and families, feel lost to them. Their only memories are of violence and war. If they are to be given a chance to rebuild a future, "the world must be allowed in to see and the Tamils must be freed from the camps and allowed to return to their houses".

But those exiled to the UK only hear horror stories via phone calls from people in Sri Lanka and messages relayed through the Tamil community in the UK, of young people being abducted from the camps and of suggestions that the army is still intent on wiping out the Tamil population.

Another young woman recalls the brutality of the camps, the incessant torture which saw her whipped with canes, kept in solitary confinement, burnt with cigarettes and suffocated with a petrol-soaked bag for more than two months. She too is filled with dread thinking about what may have happened to the family she has had no contact with since she escaped to the UK last year:

"Other women who were arrested at the same time as me are still in the camps, who knows how many are living and how many are dead."

Exiled from their country and with their families feared trapped in the camps or worse, a small group of Tamils have come together in a therapeutic group established at the MF to form links between a people whose connections to all that they held dear have been severed by war.

By far what galvanises their resolve more than anything else is the determination to counter the Sri Lankan government's attempts to deny reports of torture and ill-treatment. One young man says: "There are so many more people like us, we are not the only ones, and yet the international community doesn't really know the truth." Another woman says: "This really happened to me, why shouldn't the government know it?"

With the people of Sri Lanka increasingly cut off from the outside world, it is now more important than ever that the outside world demands to be allowed in, to provide help that is so obviously needed and to see the uncensored reality.